Electrification… The greatest engineering achievement of the twentieth century. Once a mysterious and almost magical curiosity, its use has become so intertwined with modern life that most of us scarcely think about it except when it stops—when our batteries go dead, the lights go out, or an appliance decides that it just doesn’t want to turn on anymore. And if you’re the sort of handyperson who knows a volt from an amp from an ohm, then you may be acquainted with a very nifty little device called the multimeter.

For those of you not familiar with it, a multimeter is basically the engineering tricorder of our day—the closest we can presently come to the versatile, portable, handheld scanning device that Geordi LaForge used to diagnose equipment on the Starship Enterprise. You can probably find any number of videos on YouTube demonstrating how to operate it and explaining how circuits work, the water pressure analogy for voltage, Ohm’s Law, and so forth, so I won’t waste time rehashing all of that. Today’s article isn’t to teach you how to work with electricity. Electricity can be dangerous, nothing here should be interpreted as electrical advice, and you should consult a qualified person before attempting to do any electricity-related work yourself. But, that said, all of us probably handle AA batteries from time to time. And even in the humblest little electrical circuits such as use those, sometimes it’s really convenient to actually have some instrumentation instead of guessing what’s happening. And that’s what todays article is about—the geeky, empowering joy of having one (or more!) of these nifty little instruments in your life.

I’m not going to rank multimeters from best to worst or declare a winner or any such nonsense. That absurdly oversimplifies the situation. Quite the contrary, my thesis here is that there are a staggering number of options and that any one of them might be the best for you, depending on what “best” means to you. All we’re really doing here is to take a virtual stroll down the electrical tester aisle and geek out a little along the way at the many different models available. (And whereas they usually don’t like you disassembling the merchandise in the hardware store aisles, the power of the internet has found us some photos of the internals too! Be aware that products change sometimes, though.) There really are a lot of them to choose from. And there was a time when they all looked pretty much the same to me. Almost all of them will measure volts, ohms, and amps. And even a bachelor’s degree program in engineering doesn’t necessarily leave a person with much more understanding than that. I took a class specifically on the topic of instrumentation and experimentation, and at the end of that class I could have explained to you the academic theory of how these measurements worked, but I’m pretty sure I walked away from that class with no idea why there were even multiple different input jacks at the bottom of most of these devices. It’s a good thing no one ever handed me a meter with the jacks plugged in wrong! And then people gripe about how novices are always blowing fuses. (And hopefully the meter has a fuse, or you might be blowing something more spectacular.)

While I’ve tried to present accurate information below, I expressly disclaim responsibility for any errors as might exist. Double check any pertinent facts before doing anything.

So, without further ado, let’s look at some meters!

Basic Multimeters: For when you just need the essentials

The famous (or infamous) “free” Harbor Freight Cen-Tech multimeter:

Many multimeter aficionados will cringe at the inclusion of this meter, and may even have the instinct to stop reading here in contempt of an article written by someone so unsophisticated and dangerously clueless as to paste a picture of this… this… unworthy, unsafe abomination of a product at the start of the list. But, whether your feelings about it are positive or negative, I think you have to admit that its existence is pretty wild. Listed for $7 at the time of this writing, there was rather a long period of time when you could occasionally find a coupon to snag this meter for free with any purchase at your nearest Harbor Freight. There have been a number of different models over the years that differ in subtle (but potentially significant) ways, and other merchants sell meters in this extended family under the names DT-830B and DT-830D. The whole lot is frequently derided as unreliable and dangerous—and there can be little doubt that they have a lot more potential to fail in spectacular and hazardous ways than the other meters we’ll look at—but it’s hard not to have some admiration for the fact that we’re living in a time when you can get a fully functional multimeter for so cheap that you can basically regard it as disposable. Indeed, some people report that they’ve chucked it in the garbage rather than replace the battery when it went dead. I find that wasteful and sad, but it does underscore how incredibly accessible these meters have made electrical instrumentation.

Word is that manufacturers have been trying harder and harder to cut corners over the years. Some reports show fuses that are soldered into place, lacking the glass housing, or even entirely missing. The trimpot has reportedly disappeared in later designs. And with the coupon to get it for free with purchase seemingly having become a thing of the past, it’s sounding like Harbor Freight, at least, may be starting to move on from the era of churning out large quantities of low quality junk destined to quickly end up in the rubbish bin. And if so, that’s probably a good thing for us as a society. But, if nothing else, this meter is one for the instrumentation history books. There was a time when someone might have told you that to test if a wire was live you should brush it quickly with the back of one hand whilst keeping your other hand in your pocket and wearing good shoes. Compared to that old-school handyman’s approach, even this meter starts to almost look safe. At least the voltage range is usually fused if you got your meter from a respectable manufacturer, so if you’ve got it set correctly (and that’s a nontrivial “if” for a meter so inexpensive as to be likely to end up in the hands of a great many novices) then the potential for catastrophe is at least somewhat bounded. And hopefully a novice is working on something more like a small battery-powered circuit and less like energized utility power. Sometimes a simple continuity test on non-energized wires is all you need to figure out why a piece of equipment stopped working. Failed switch? Blown fuse? Broken wire? All identifiable with a basic multimeter without utility power coursing through the equipment at all. Most of these models (except the 830D) don’t have audible continuity, but they measure resistance. And if the resistance is low then you have continuity. The audible tone that most other meters make is mostly for convenience—and don’t get me wrong, it is very convenient. Some people also seem to really despise having to pick the range manually. I can’t say such a thing has ever bothered me much. If you really have no idea how much voltage you’re about to measure, start high and work your way down—you’ll find it. For as much as auto-ranging meters have become the standard in today’s world, that’s the trade-off you make when you buy a $7 meter. Just the fuse in my Fluke costs more than that. Oh, and you see that input jack marked 10ADC? Novices should put a piece of electrical tape over that. That’s the self-destruct socket. We don’t use that socket unless we’re sure we know what we’re doing. Got it? Good.

It may be the humblest of multimeters, but did you know that it actually has some royal blood in its history? The chip running the show in this little guy (and supposedly a lot of other low-end meters too) is reportedly nearly identical to the chip behind the great Fluke 8020A, “the world’s first successful handheld digital multimeter” (https://www.fluke.com/en-us/learn/blog/digital-multimeters/multimeter-history, https://www.eevblog.com/forum/testgear/history-of-the-fluke-8020-series/). Evidently there was a bit of a legal kerfuffle back in the day over the chipmaker selling to other companies what was essentially a technological marvel of the time developed specifically for Fluke, but we may have that chipmaker to thank for the fact that even dirt cheap multimeters actually usually aren’t half bad in terms of accuracy if you can keep them physically in working order. I won’t go so far as to join the chorus declaring any of them to be “just as good as” Fluke, but–for whatever associated evils you might be able to point to–it is nonetheless impressive what can be done sometimes when good designs aren’t locked up in a company’s proprietary vault of intellectual property.

In any event, the word is that the input impedance is only about 1 MegOhm, so that presents a little bit of a gotcha, particularly in low-energy electronics: You can change the outcome by observing it. Suppose you’re probing the voltage drop across a 1 MegOhm resistor—you’ve just halved the effect of that resistor by virtue of putting your meter in parallel with it. That might be a big deal in some circuits, and not just in terms of measurement error or changing the behavior—you might actually damage something if you’re performing brain surgery on a delicate enough circuit. Electronicists traditionally want their meters to have as much impedance as possible (10 MegOhm being the typical expectation of a “good” meter). So if that’s the kind of work that you’re doing then of course you don’t want to be using this meter. But if that’s the kind of work that you’re doing then you probably already know that. And in the old days of analog (moving needle) voltmeters, people got by with less input impedance than that. And sometimes you actually want low impedance! Today’s instruments are so sensitive sometimes that they can pick up on things that almost aren’t even there. And if you’re not doing really delicate work, having a meter that dutifully reports such “phantom voltage” is only going to confuse you and slow you down. More on that a little later!

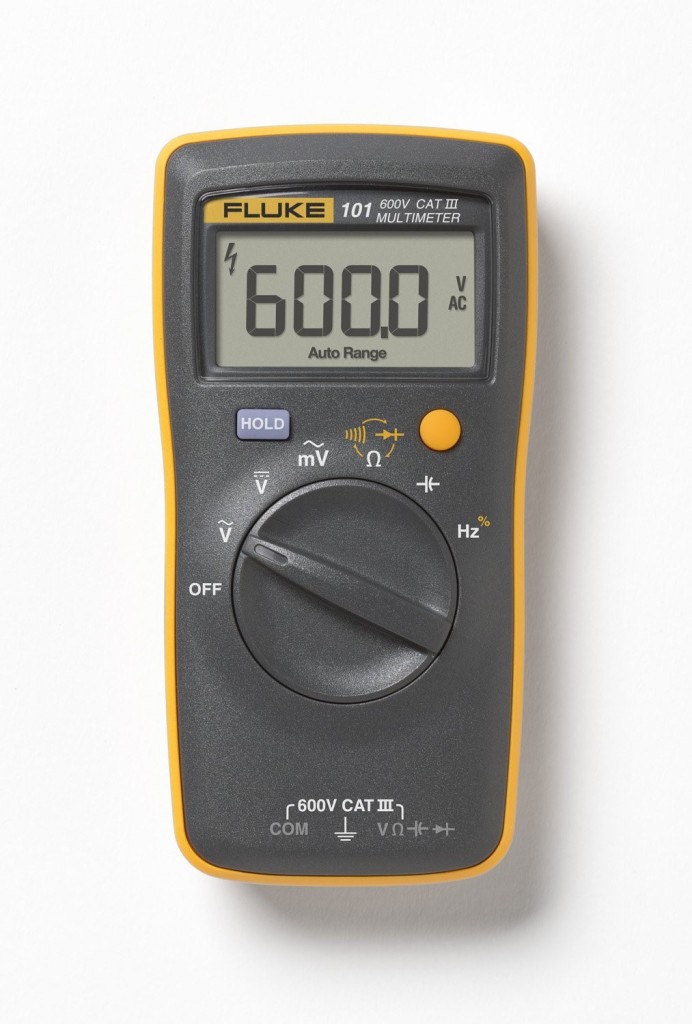

Fluke 101:

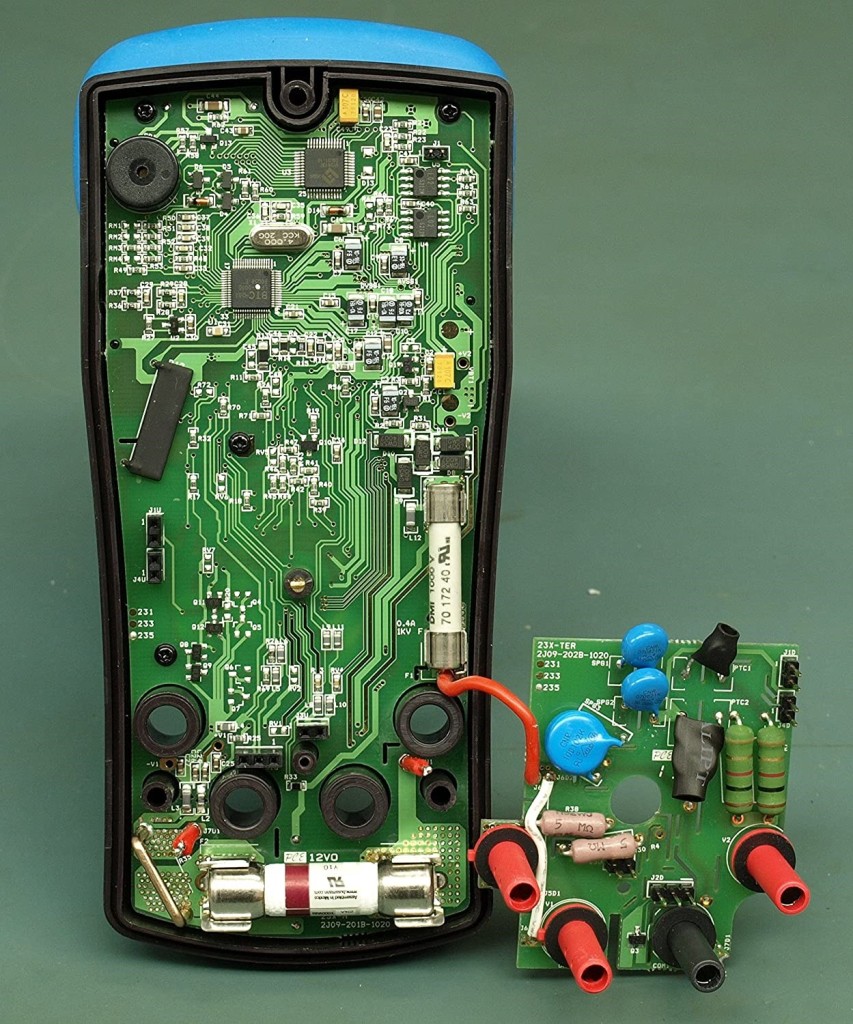

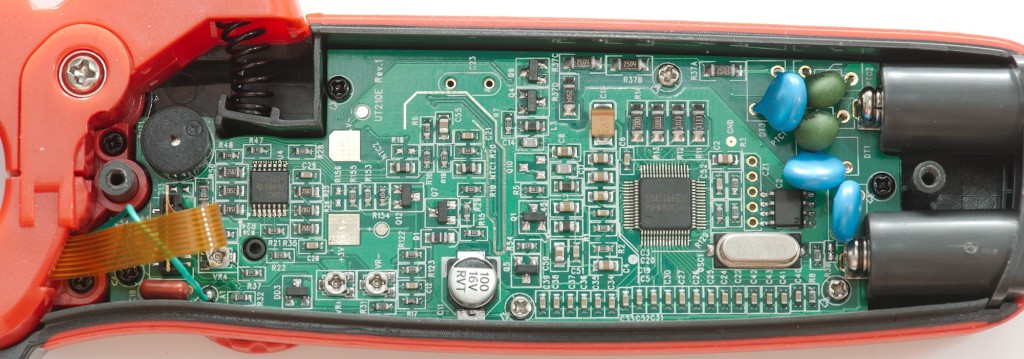

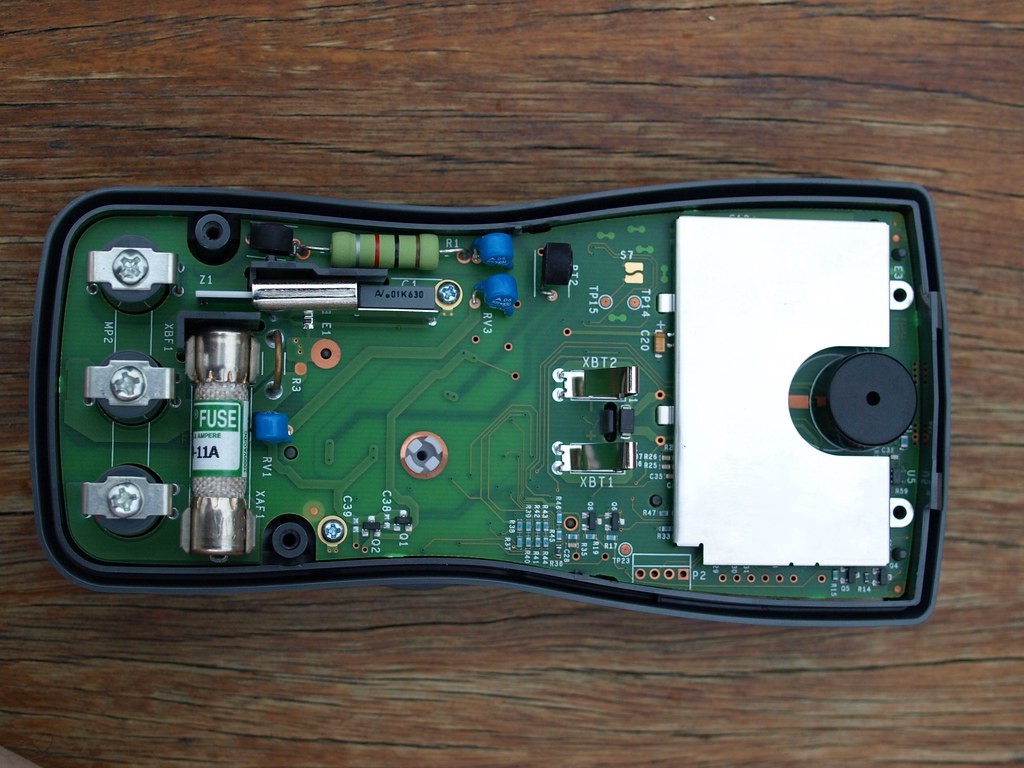

At sort of the opposite end of the spectrum of basic meters is the Fluke 101. While not officially intended for (and thus not likely to have fruitful warranty experiences in) markets outside of China, it can nonetheless be found on Amazon in the US for about $50, sometimes a bit less, as of this writing. While playing with electricity is never something to be taken lightly, this is a meter that I wouldn’t feel too apprehensive about handing off to a would-be technician who isn’t exactly the brightest bulb. You remember that self-destruct socket we talked about on the Harbor Freight meter? It doesn’t exist here. Fluke is pretty much the gold standard when it comes to multimeters, at least in the United States. They’re not cheap. Almost any other brand will give you better bang for the buck in terms of capabilities. But they have a solid reputation for being top-notch in robustness and reliability. Fluke is the brand that one would ordinarily turn to when they can’t afford to mess around—when it just has to work. Some Fluke fans turn up their noses at these made-in-China Flukes, and it’s probably fair to say that they aren’t quite the upper echelon that the US-made Flukes are, but teardown pictures and videos posted online reveal some pretty impressive input protection compared to other $50 meters from other manufacturers that have more bells and whistles. You see that gigantic resistor (light green with stripes), MOV (darker green round thing), and pair of PTC’s (blue round things) at the left of the picture? That is how input protection is done! (No fuse needed on the inputs in this particular case because this meter doesn’t sense current.) The input impedance is nominally greater than 10 MegOhm, so it’s appropriate for electronics work. The price tag makes it a tough sell to hobbyists and DIYers, but to the right beholder it is a thing of beauty that there even exists a Fluke that can be had for “only” $50. Adam Savage of Mythbusters fame made a video gushing over this littlest, cheapest of Fluke meters (https://youtu.be/K9fQn1bQVsQ). Those of us in certain professions have been conditioned to get warm fuzzy feelings when we see the gray and yellow of a Fluke. If you get it, you get it. And if your needs aren’t particularly complex and you can tolerate not being able to measure current (at least not without rigging up an external shunt), then you could really imagine this being the only meter you ever have to buy. It even does capacitance! And if the number of pre-owned, decades-old Flukes for sale that still work is any indication, it might even pay for itself in the long run compared to buying a cheap piece of junk that you have to replace every five years. If you are serious about the #buyitonce mentality, then it’s hard to pass up a Fluke.

Klein MM300:

It can be hard to find a meter much below $50 that looks like it has respectable input protection—most people don’t take their meters apart, so it’s an easy place to cut corners. I’m no expert in such things, but this manual-ranging option (for $30 at the time of this writing) looks respectable enough to me. I see what look like both a PTC and a MOV near the inputs, the latter of which too often gets omitted. Both inputs are fused, and the fuses look respectable too. (The really cheap ones are usually glass.) The battery test mode for 1.5V and 9V batteries is a fairly handy thing to have around the house, and it’s the sort of thing that you don’t really see on more expensive meters. Unlike the regular voltage range, this mode deliberately draws a little bit of test current so you can see how much voltage the battery can put out under load—Sometimes a dying battery will read a solid 1.5V when not in use but then plummet if you actually try to use it. I wasn’t able to find any report of this thing’s input impedance, but based on the resistance range it’s probably a fair bet that it’s low-ish, somewhere in the ballpark of 1 MegOhm. And that would make sense. Klein is mostly known for electrical (not electronics) work.

General-Purpose Multimeters

Brymen BM-235:

This is the multimeter of EEVBlog fame. Leave it to Dave to pick an awesome meter. What is perhaps most impressive here is not that it’s a pretty darn good electronics meter for a decent price ($140 as of this writing), but that it’s actually got to be about one of the most generically useful multimeters you can find. If you had to pick a truly general-purpose multimeter with absolutely no foreknowledge of how it was going to be used or to what type of job it was going to be applied, I think something like this would have to be your choice. I don’t think you could find this combination of functions anywhere in the Fluke lineup, at any price. It’s got low-impedance voltage measurement and non-contact voltage detection for electrical jobs. It’s got capacitance and microamps for HVAC work. High-impedance voltage, milliamps, and microamps for fine electronics. It does True RMS if you happen to be measuring a non-sinusoidal AC signal for whatever reason. The only non-esoteric thing it’s really missing is an amp clamp, but you could find one as an accessory if you really needed to. No meter is going to be able to do literally everything, but I feel like this one does everything you could reasonably ask of a “standard issue” multimeter. And that’s a surprisingly hard combination to find from a trustworthy brand, so my hat’s off to Brymen on this one. They’re a name Americans may not have heard of because Brymen doesn’t actually market this meter in the United States, but the EEVBlog version is available on Amazon nonetheless. And the similar BM-257S can be found rebadged as the Greenlee DM-510A. And Greenlee might be a little more helpful if you were to find yourself seeking warranty service in the United States.

Ames DM1000:

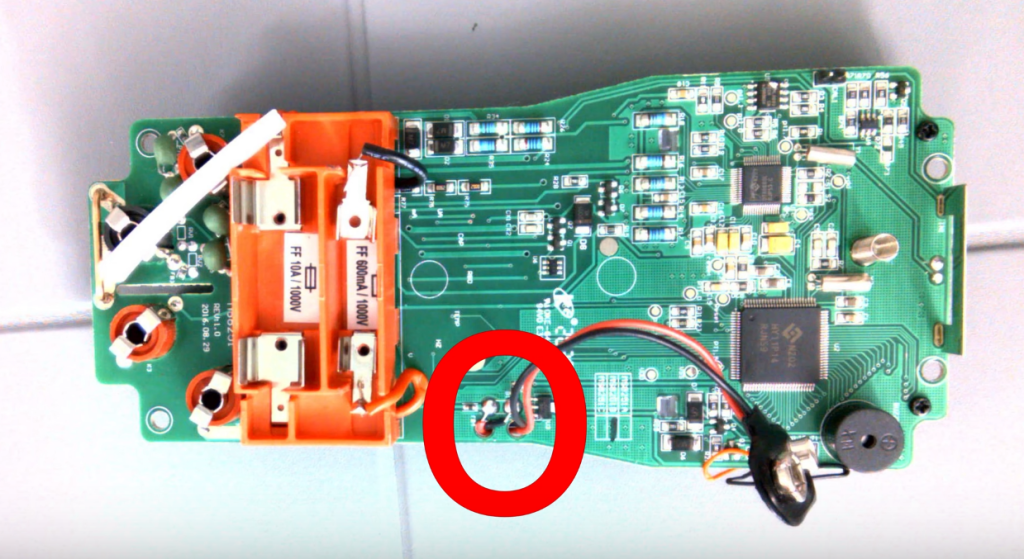

This is supposedly a rebranded Mastech 8251B, but did they seriously omit the gas discharge tubes? It’s hard to see in the only teardown video that I can find, but I think they did. (Near the black input jack—ignore the circled battery connection. Best teardown photo I could find.) And this is supposed to be a Cat IV meter. Leave a comment if I’m overlooking something. I mean, I know they say it’s independently tested, but that just doesn’t feel right and it makes me sad. And it makes me wonder if they cut other corners that I can’t see. Still, the $75 price tag sure is tempting… How handy are you with a soldering iron?

Technically, Harbor Freight labels this an “Electrician’s HVAC Contractor” meter, so there’s an argument to be made that it actually belongs in the next category instead of this one. But, to be fair, it has pretty much the same capability set as the BM-235. And that’s awesome for electrical and HVAC jobs, but it’s awesome for other jobs too.

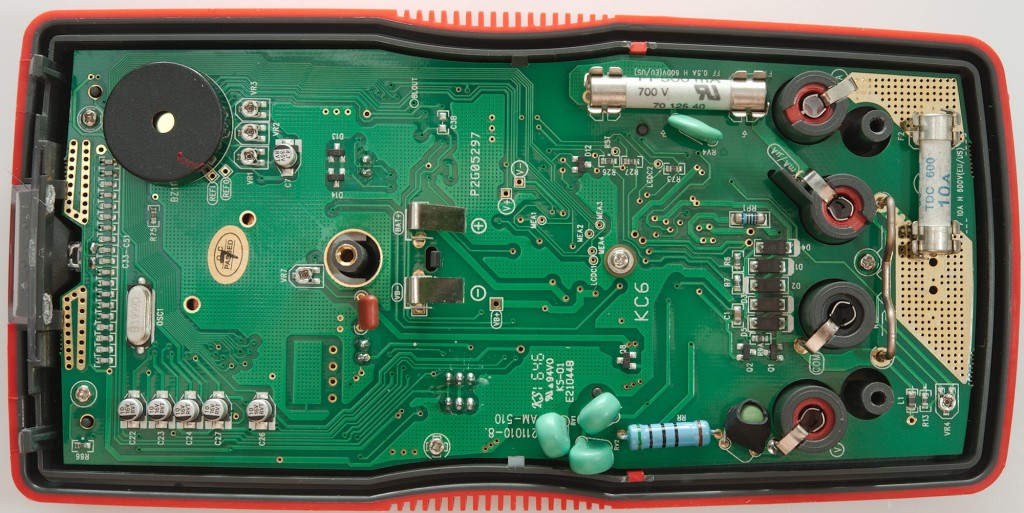

Amprobe AM-510:

Amprobe is actually related to Fluke, although I’m having trouble finding a clear explanation of exactly what that relationship is. Some people say Amprobe is owned by Fluke, others say Amprobe and Fluke are part of the same group. Fluke’s website states that Amprobe is “part of the Fluke family”. Amazon’s Amprobe page says that “All Amprobe tools are designed, tested, and supported by Fluke engineers”. Like all the meters that I’ve lumped in under this “general purpose” category, this one measures capacitance, which is probably one of the first things that might drive a user here as opposed to the “basic” category above. This meter also has the uncommon 1.5V/9V battery test feature mentioned earlier. About $50 at the time of this writing.

Uni-T UT210E:

This is a pretty neat little meter. For about $50, you get a convenient, tiny little meter with reasonable-looking input protection that does True RMS volts, ohms, capacitance, non-contact voltage detection, and has an amp clamp that works on both AC and DC and can range down to 2A for small-ish readings or up to 100A for large-ish readings – breaking circuits and blowing fuses is a thing of the past with this modern marvel! (As with all amp clamps, you have to clamp around just one conductor—if you go around an entire cable with both hot and neutral then they’ll cancel each other out and you’ll read zero.) It’s not going to be able to compete with the really fine measurements of a more classical meter, especially on the milliamp or microamp range, but for a lot of general-purpose applications you don’t need it to. A “Pro” version is also available for $10 more that additionally measures frequency, has a wider capacitance range, and is allegedly faster. Its 10 MegOhm input impedance does leave you susceptible to phantom voltage but is good for not loading the circuit you’re trying to instrument. I wish they’d take a page from BSIDE’s book, who knocks off this form factor to make something that does offer a LoZ setting to give you the best of both impedance worlds, but they cut corners on input protection.

Specialized Electrical and HVAC Meters

Fluke T6-600:

$178 at the time of this writing. Technically, Fluke doesn’t call this one a multimeter. They use the word “tester,” and so it’s easy to miss this one while you’re multimeter shopping. I suppose the distinction in terminology is meant to acknowledge that this isn’t the same precision instrument that the “real” multimeters are. For one thing, you’re only going to be measuring voltage in one-volt increments. That makes it completely useless for determining if an alkaline battery is any good, for example, and awfully crude for diagnosing automotive systems. And if I’m reading the specs correctly, although the uncluttered knob looks like what you’d find on an auto-ranging meter, this one technically isn’t in the sense that it only has one range for each of its modes. So this meter is a bit of a blunt instrument and isn’t for the jack of all trades. But what it is is a purpose-built electrician’s daily go-to device with everything they need and nothing they don’t. And there’s a certain elegance to that simplicity. There are only three positions on the dial: volts, amps, and ohms. Nothing extraneous to trip you up or slow you down. And its input impedance of around 1 MegOhm is right around the sweet spot for this sort of work—high enough that you probably won’t trip a GFCI if you probe between hot and ground, but low enough that you hopefully won’t lose time hunting down phantom voltage that doesn’t matter. Word is that the “Field Sense” no-touch voltage measurement is a little dodgy and you have to understand how to work it right, but honestly the fact that it can even get things mostly right most of the time is a modern marvel. We’re talking about not just identifying whether a wire is hot or not (like those non-contact voltage detector pens that, come to think of it, everyone also likes to complain about) but actually estimating the numerical voltage on that line without coming into electrical contact with the conductor. If you really don’t want that feature, you can get the older T5 instead. Like the 101 earlier, the T5 is one of those meters that one doesn’t worry too much about handing to a would-be electrician who isn’t the brightest bulb. Either way, though, you’ve got a meter designed for the electrician who needs to get in, get out, and get on to the next job. The skinny shape with probe holder on the end is perfect for poking around when you’ve only got two hands. The current sensing (AC only) doesn’t involve undoing the wire nuts or putting your meter inline with your AC load (because, honestly, that’s fine for making precise measurements on a low-voltage electronics project, but does anyone really think that sounds like a good idea with mains electricity?). You don’t even have to squeeze a trigger to open a clamp—it’s an open jaw, ready to slip the wire right in. An HVAC technician might long for capacitance and microamp ranges, but this really isn’t an HVAC meter. This is an electrician’s meter. And while a surprising number of HVAC technicians do seem to use the T5, maybe because it’s comparatively wieldy and inexpensive, I feel like they probably should be using something more like a Fluke 324.

For input protection, it appears to have a gigantic resistor, a PTC, and a gas discharge tube. Also available in T6-1000 for those that need to work on higher voltages.

Ames CM200A:

It’s hard to find teardown photos of some of the less famous Harbor Freight meters. Unlike the Cen Tech line that’s been around forever, their newer Ames line purports to be professional grade. And I have to admit I was impressed at the size of that MOV for the price point (about $50 at the time of this writing). The form factor is similar to the Fluke T6, although you don’t get the handy probe holders, which is kind of disappointing because I still only have two hands. But unlike the Fluke, this one caters to both electrical and HVAC needs—adding the microamp, capacitance, and temperature ranges that were so conspicuously missing on the T6. It doesn’t have the FieldSense voltage-estimating magic of the T6, but it does have a built-in noncontact voltage detector to give you a basic hot-or-not verdict. It gives you your choice of high- or low-impedance voltage sensing so you can do whatever the job demands, and it actually reads fractions of a volt and has multiple different ranges internally like a proper multimeter should (except for amps, where it’s still just a single 200-amp range). It’s pretty much the perfect combination of capabilities for electrical or HVAC work, and for a mere $50 at the time of this writing! I don’t know how long it would stand up to the rigors of daily bang-around use, but if you were starting up an electrical contracting company from scratch and you really needed something to get you going on a tight budget, I suspect you could do a lot worse than this. This appears to be a rebadged Mastech MS2601.

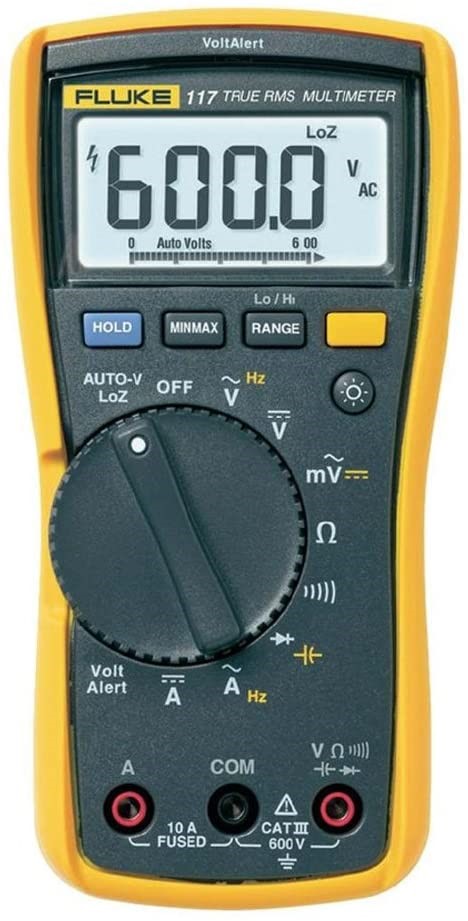

Fluke 117:

A Chinese-made Fluke presently going for $207, this one is not unlike the BM-235 but with the omission of the features that you’re not actually likely to need for electrical work. So I think it’s completely fair that this one gets marketed as an electrician’s meter. A related meter, the 116, trades in the non-contact voltage detection and amp range for temperature and microamps. That one is intended for HVAC work. With Fluke, you kind of have to pick your specialty. And I don’t mind that so much as the fact that the 117 alone still doesn’t necessarily get the job done for an electrician. It’s missing an amp clamp. You could buy a 323 or 324 instead, but then you don’t get non-contact voltage detection or low-impedance voltage. And, if you haven’t noticed by now, I’m a big fan of low-impedance for electrical work. In my more cynical moments, it feels like Fluke is actively scheming to make sure electricians have to buy at least two separate meters to get their job done. And that’s not even counting separate equipment like an insulation tester or whatever other specialized tools you might need.

But I use a 117 myself on a regular basis. It was this meter, with its dual impedance options, that taught me firsthand just how much impedance matters. I still start off on high impedance as a matter of habit, but whenever I get a reading that doesn’t make any sense I know to switch to low impedance straight away. I’ve seen a circuit with a loose neutral go from about 60 VAC under high impedance to 0 VAC under low impedance. Another time, I thought for a moment that a Romex cable might have been damaged when a steel plate that it ran behind showed an even higher voltage than that to the concrete floor. But low impedance made that go away too. Just some capacitive coupling–not mains electricity leaking out and waiting to shock anyone!

Klein CL700:

Now this is an electrician’s meter. Why can’t Fluke make something like this? All the important features of the Fluke 117 plus an amp clamp (with both a 60A and 600A range) in one multimeter for $100 at the time of this writing. (And the CL800 adds DC current capability to the amp clamp, if you need that.) Okay, it is missing millivolts. But am I wrong here? Fluke actually sells a 117/323 “Electrician’s Combo Kit” because they seem to know that it takes two Fluke meters to cover the basic breadth of work of an electrician? Maybe there’s no point in quibbling over it because an electrician is almost inevitably going to amass a collection of multiple meters anyway. But it’s a little frustrating to me that Fluke doesn’t make something like this at any price. Maybe they will someday—when you’re known for steadiness and reliability, you can only update your product line so quickly. And still no microamps here, so it may not be suitable for certain HVAC work.

Electronics Multimeters

Brymen BM-786:

While a few of the meters listed in the general-purpose category above could potentially serve a person just fine in electronics work, at about $185 at the time of this writing, this is the sort of instrument one buys if one needs a high-quality, precise, reliable instrument but isn’t quite driven to the Fluke it-just-has–to-work price point. Most of what someone will get excited about on any of the meters in this category comes from diving into the specs, and I know better than to open that can of worms. If you’re doing something in this class, then I’m not really in a position to make generalizations about your needs and you’re going to have to study the specs and figure out if it’s exactly what you need. Since input impedance is one of the things that I like to harp on, though, I am obliged to mention that – if you can find it – the BM-789 adds the LoZ voltage setting that I love so much. But I suspect most electronicists don’t often have need of that?

Aneng AN8008:

This is the cheap multimeter that’s been making waves among EEVBlog followers. As of this writing, it’s about $28 on Amazon, and less than that on AliExpress. The input protection leaves more than a bit to be desired. The fuses are tiny, the only PTC isn’t located anywhere near the inputs, and there’s no MOV that I can see. And the price tag, while low, isn’t so dirt cheap that I’d be willing to just shrug and toss it into the rubbish bin if it stopped working. Wouldn’t it be better to put those $28 toward something you can be a little more confident will last for years and years? But if you really only work on low-energy circuits, this is a pretty tempting little instrument. It’s 9,999 count and it’s true RMS. And if you’re running something like a robotics club, for example, where hurried, inexperienced people are going to use and abuse and damage their instruments despite your best effort to limit the chaos, then maybe this is a happy little medium between fully disposable and decently functional. Be aware that the milliamp mode only has a single, 1,000 mA range—they skipped 10 and 100 mA, so you do lose precision right around a pretty important regime for many electronicists.

Fluke 87-V:

This one hardly needs to be mentioned, because if you need it then you already know what it is. But I would be remiss if I ended our walk down Multimeter Lane without visiting the flagship of multimeters. This is quite possibly the most famous multimeter in the world, descended from the original Fluke 87 that took the world by storm in the 1980’s. This is a big, heavy, first-class industrial meter—the kind that you get when you’re launching something into outer-freaking-space and you need a miles-long paperwork trail justifying that you know your system will work. $420 on Amazon at the time of this writing.

Conclusion

Whew! That was a somewhat longer blog entry than I thought it would be! And that was nowhere near an exhaustive market survey—I didn’t even try to cover automotive meters, pocket meters, or those strange newfangled push-button “smart” meters! But hopefully it gives you a taste for the diverse array of different flavors of multimeters out there. If you came here hoping this article would help you narrow down which one to buy and you instead left with your head just spinning from all the options – well, you and me both, my friend! It depends on what you’re doing, how you’re doing it, and even your philosophical views toward test equipment and money in general.